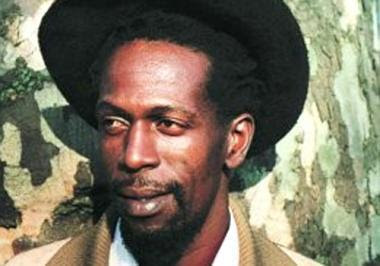

This is a reproduction of Diego Velázquez's painting An Old Woman Cooking Eggs which is in the National Gallery Of Scotland.

In his collection of short prose pieces themed around 'bequests' - from political commitment and atheism, to how to tell a good restaurant and the lost joys of outdoor sex - Where There's A Will (50p last week from my local charity shop) John 'Rumpole Of The Bailey' Mortimer writes so beautifully about it in two pages I found so right that I've had a strong compulsion all week to quote from it at length here, and have now given into it.

-----

"To the proud stones of Greece and poet's imaginings other bequests must be added to make up the superhuman, mirror-resembling dream. I have a gallery of pictures in my head so that, if I went blind, I could still enjoy them. I would direct you to the National Gallery of Scotland, one of the least exhausting, most rewarding collections in the world that, in a few comfortably intimate rooms, contains more masterpieces to the square foot than you have the right to expect. Among the saints and great ladies, the naked beauties and the suffering martyrs, taking her rightful and honourable place is an old woman cooking eggs.

Velázquez went to Madrid in his twenties and very soon became a court painter, truthfully observing pale-lipped kings, overdressed infantas and the sad faces of the palace dwarfs. Before that he served five years apprenticeship to a Sevillian painter whose daughter he married and, taking time off from his religious paintings, looked hard and clearly into the kitchen.

The everyday scene in the Edinburgh gallery is lit in the sort of way the painter learned from Caravaggio, so that the objects in the kitchen achieve an extraordinary significance. The old woman has an aquiline, Sevillian nose, sharp eyes, a firm mouth and grey hair. The white cloth on her head and shoulders falls into soft folds on the coarse material of her dress. She has the suntanned, loose-skinned hands of her age but one of them holds an egg carefully and the other delicately points a small wooden spoon, ready to drip a little oil in which we can see eggs setting, their yolks and whites clear in the pan. An unsmiling peasant boy is carefully dripping in more oil and the old woman watches him anxiously. The miracle of the painting is in the exact and loving re-creation of oil, eggs and earthenware, the shine on the brass pots, the shadow of a knife on a china dish, the feeling of flesh and cloth. Forget all concerns about blessings or terrifying events occurring beyond the grave, this picture celebrates the significant moment when the eggs start cooking and another spoonful of oil has to be dribbled in.

The old woman, or someone very like her, turns up again in another of Velázquez's kitchen scenes, this time in London's National Gallery. Her head is again covered with a white cloth and she is instructing a sulky and unwilling Martha on how to pound garlic and cook some fresh fish and more eggs. In a mirror we can see that Jesus has arrived at the door and is about to engage the no-doubt eager Mary in a conversation about life, death and the miracle of salvation. Far more interesting to the old woman is seeing that the fish is cooked properly, dinner is on the table in time and the garlic is well-pounded.

Velázquez went on to paint grander scenes. Venus, the goddess of Love, lies naked, admiring herself in a mirror held up by Cupid, presenting to us her splendid bottom. He painted kings on prancing horses and military triumphs such as the surrender of Breda and royal persons hunting wild boar. He became famous in Italy for his portait of Pope Innocent X, a merciless military commander. His final act was to decorate the Spanish Pavilion on the Isle of Pheasants for the marriage of the Infanta Maria Theresa.

Through all these great events, wars and festivals, the lives of kings and Popes, the old woman remained busy in the kitchen, dealing with the important things in life, such as the exact amount of olive oil needed to fry eggs."